Speculation abounds as to identity of the anonymous author of a 2018 New York Times op-ed and recent book critical of President Trump. A former speechwriter for President Bill Clinton, David Kusnet, suspects that “Anonymous” is Guy M. Snodgrass, a former speechwriter for then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis, based on Kusnet’s “close reading” of the aforementioned pieces and Snodgrass’ book Holding the Line, which also criticized President Trump. Mr. Snodgrass at first courted the speculation, then denied authorship. Anonymous has pledged to unmask himself or herself in the near future.

An investigation of the authorship question through natural language processing, or NLP—broadly speaking, the analysis of human language by computers—illustrates the application of some rudimentary NLP techniques.

I bought the two books, had them scanned, and performed optical character recognition (OCR) to extract the text into computer-readable form. Apart from a cursory check of the OCR to confirm its high quality, I haven’t read either book.

Natural language processing can identify writing characteristics such as sentence length, words per sentence, and punctuation per sentence. Such characteristics may leave a stylistic signature, much as objects emanate heat signatures. Six such traits for each book appear below:

| Stylistic Trait | A Warning, by Anonymous | Holding the Line, by Guy M. Snodgrass | Holding the Line as a percentage of A Warning |

| Words per sentence, mean | 17.28 | 17.98 | 104 |

| Words per sentence, standard deviation | 12.58 | 12.49 | 99 |

| Lexical diversity (number of different words used:total number of words used) | 0.147 | 0.123 | 84 |

| Commas per sentence | 0.8 | 0.98 | 123 |

| Semicolons per sentence | 0.02 | 0.014 | 70 |

| Colons per sentence | 0.04 | 0.11 | 275 |

Apart from a noticeable difference in colons per sentence, the other stylistic traits match up quite similarly.

Natural language processing can also identify words as parts of speech, such as singular noun, plural noun, foreign word, verb, verb in past tense, and so on, for dozens of parts of speech. The frequencies of various parts of speech used by an author also leave a verbal “signature.” The per-sentence frequencies of six common parts of speech for the two books were as follows:

| Part of Speech | A Warning, by Anonymous | Holding the Line, by Guy M. Snodgrass | Holding the Line as a percentage of A Warning |

| Noun, singular | 4.04 | 4.63 | 115 |

| Noun, plural | 0.93 | 0.74 | 80 |

| Proper noun, singular | 0.06 | 0.07 | 117 |

| Determiner | 1.59 | 1.54 | 97 |

| Preposition or subordinating conjunction | 1.7 | 1.8 | 106 |

| Adjective | 1.8 | 1.9 | 106 |

The part-of-speech signatures appear even closer than the stylistic signatures, with no salient discrepancies leaping out.

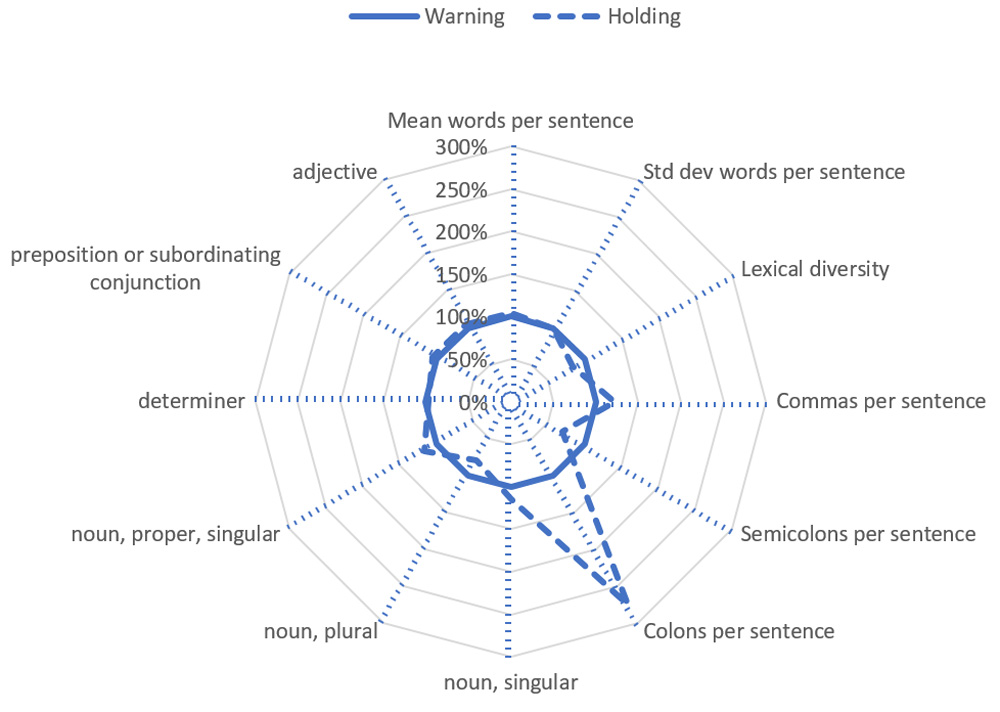

The chart above offers a graphical view of these stylistic and part-of-speech traits. A Warning sets the baseline value for each trait, with the corresponding value for Holding the Line expressed as a percentage of the value for A Warning. As noted above, Anonymous and Mr. Snodgrass match up closely with the lone exception of a discrepancy in colons per sentence.

It is worth noting that these simple signatures suffice to identify with over 85% accuracy the three Federalist Papers authors, another famously anonymous work, using a simple model.[1] Of course, attributing authorship of the Federalist Papers from among three choices, each with multiple writings as bases of comparison, differs from identifying Anonymous among a multitude of possible authors. But the exercise gives a sense of the use and capabilities of NLP in a similar context.

Note the many points of possible failure in this analysis, regardless of whether Anonymous is Mr. Snodgrass. For example, an editor or even two different editors may have ironed out stylistic differences for mainstream readability and appeal. Mr. Snodgrass has written only one book for attribution, and may have changed his writing style from one to the next. He could purposefully have changed his writing style in order to obscure authorship. Anonymous could purposefully have imitated the style of Holding the Line to disguise himself as Mr. Snodgrass. Two different publishers likely had different editors revise the books. One book may, by coincidence, have more tables, footnotes, endnotes, or the like, which distort the signature measurements found only in the prose—as I noted, I did not read either book, nor did I endeavor to control for such factors.

Note also that this is a fairly simple analysis, involving only two samples of Mr. Snodgrass’ writing across a handful of NLP measurements. The analysis could be expanded, and potentially improved, in many ways. In addition to correcting for some of the possible points of failure noted above, a broader, forensic analysis could encompass numerous other factors and traits, such as:

- More writing samples from Snodgrass, potentially including an article he wrote for the Naval War College Review and the New York Times op-ed, although these are not books.

- More NLP traits, such as additional parts of speech, measured on more dimensions, such as per-page and per-chapter.

- Sentence structure and syntax.

- The textual clues which helped lead Mr. Kusnet to identify Mr. Snodgrass: “short sentences, one-line paragraphs, the frequent use of alliteration . . . ‘reversible raincoat’ constructions . . . [and repetition of] the same words or phrases in different contexts.”

- Statistics for these traits among books generally, or among nonfiction, or among recent political nonfiction. The greater age and shorter length of the Federalist Papers degrade their value as points of comparison, handy and familiar though they may be.

- Writings, especially books, from other potential Anonymous authors.

The last two possibilities point to the next natural step in this analysis: to analyze one or a handful of recent political books, selected from Anonymous candidates if possible. The cogency of Mr. Snodgrass’ close match with Anonymous depends on whether others can be found who match closely as well. I have not sought out any such books for scanning and analysis, but may do so in the future given sufficient interest.

[1] The model involves the following: For each author, find the mean and standard deviation of each stylistic trait across all papers by that author. For each paper, find the value of each stylistic trait. For each author, calculate the number of author standard deviations by which the paper stylistic trait diverges from the author’s mean. Ascribe authorship of the paper to whichever author has the lowest sum of squared standard deviations across all traits. Standard deviations are used in order to normalize scores to the same unit. Significantly more complex models are easy to conceive.